Introduction

Polyvagal theory is quite “HOT” at the moment. Charts and ladders with traffic light colors are flying at you left and right. On one hand, this is quite understandable, but it brings with it a risk of excessive oversimplification, and that’s not good for anyone.

Why not? That’s what this article is about.

As you can see, there’s a (1) following the title of this article. I have enough material about misunderstandings for a few more articles. In this article, I describe three of them. To be continued, therefore.

If you’d first like to know more about polyvagal theory (helpful), check out the basic article I wrote about it.

The Appeal of Polyvagal Theory

When Stephen Porges first published on polyvagal theory (PVT) in 1994, he had no idea that his theory would be so embraced by therapists, particularly body-oriented therapists. The theory retrospectively explained what they had been observing in their clients for years.

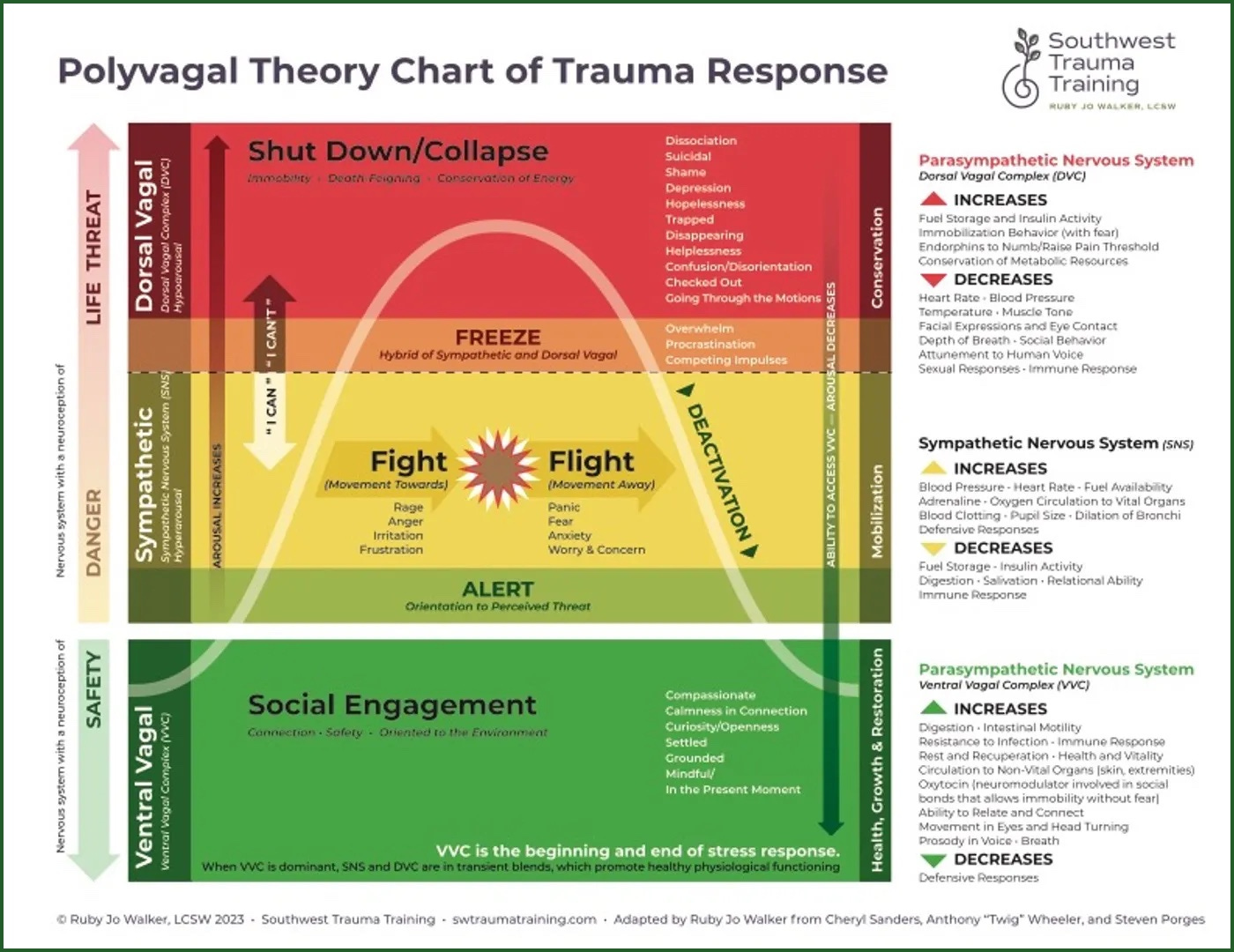

Moreover, the theory is also easy to make comprehensible, with three structures that form the autonomic nervous system (ventral vagus, sympathetic, and dorsal vagus) and three corresponding basic autonomic states (respectively: connection, action, and shutdown). Add a hierarchical list, a scanning system, and a regulatory system, and you can explain much human behavior and interaction.

All of this can also be explained quite well to people without knowledge of how the nervous system works.

Is Polyvagal Theory Simple?

A rhetorical question. The fact that something can be easily divided and explained to others doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a simple theory. Consider this: Stephen Porges is now 80 years old and started philosophizing about the autonomic nervous system at age 21.

Recently, he wrote an extensive article about “how it came to be,” from which I quote a first paragraph:

Polyvagal theory (PVT) emerged from my efforts to bridge psychological processes and autonomic function, drawing on insights from neurophysiology, neuroanatomy, clinical medicine, and the study of brain–body connections across disciplines. Developing this theory illuminated a fundamental challenge in science today: disciplinary silos often restrict collaboration and the integration of knowledge, as specialized methods and language can inhibit the exchange of ideas. When research remains isolated, advancing collective understanding becomes more difficult. This study examines the development of PVT and articulates its core principles in light of interdisciplinary engagement—particularly with colleagues unfamiliar with the theory’s foundational literature. Bridging such gaps requires not only sharing knowledge but also cultivating openness to new perspectives, intellectual flexibility, and a spirit of curiosity about ideas that challenge established assumptions.

I think we see an important aspect of polyvagal thinking described here, namely the interdisciplinary character and the investigative, curious, and flexible mental attitude needed to connect all those different perspectives and knowledge. There aren’t many scientists who can do that, and there are even fewer who have been engaged with it for nearly 60 years of their career.

So it’s not all as simple as it might seem when you look at the ladders and read many LinkedIn posts.

Where Things Go Wrong

Some ‘Simple’ Examples

A System Is Either On or Off

You hear it regularly when polyvagal theory is explained: when the sympathetic system goes on, the ventral vagus goes “offline,” or name any other combination. The autonomic nervous system is portrayed as a series of three switches that are either on or off.

This is where the ladder model falls short. It encourages this suggestion. You can, of course, argue that combinations of two active systems are also possible on the ladder, precisely in a transition area. But the degree to which they are active remains unclear, and not all combinations of autonomic states are possible with the ladder.

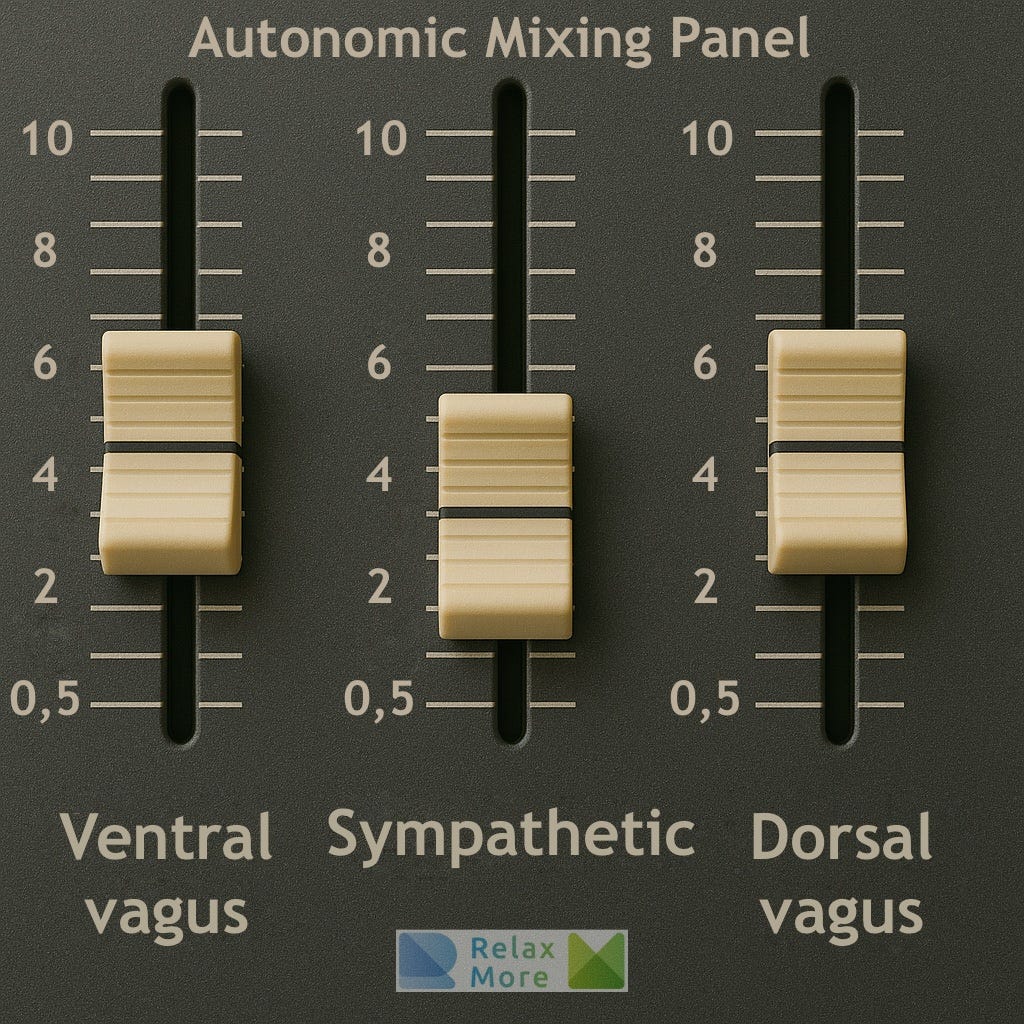

That’s why I gave the ladder a much more modest place in my training some time ago and developed an autonomic mixing panel. It looks like this:

What I wanted to make clear is, first, that none of the three subsystems can be off, and second, that many combinations of the three subsystems are possible.

Fixation on Hierarchy

One of the three pillars of PVT is the so-called autonomic hierarchy. More completely, it’s “evolutionarily determined autonomic hierarchy.” The other two are neuroception and co-regulation. The order in which I described them in the previous sentence is the order you usually hear when people describe the three pillars. But it’s not actually the correct order.

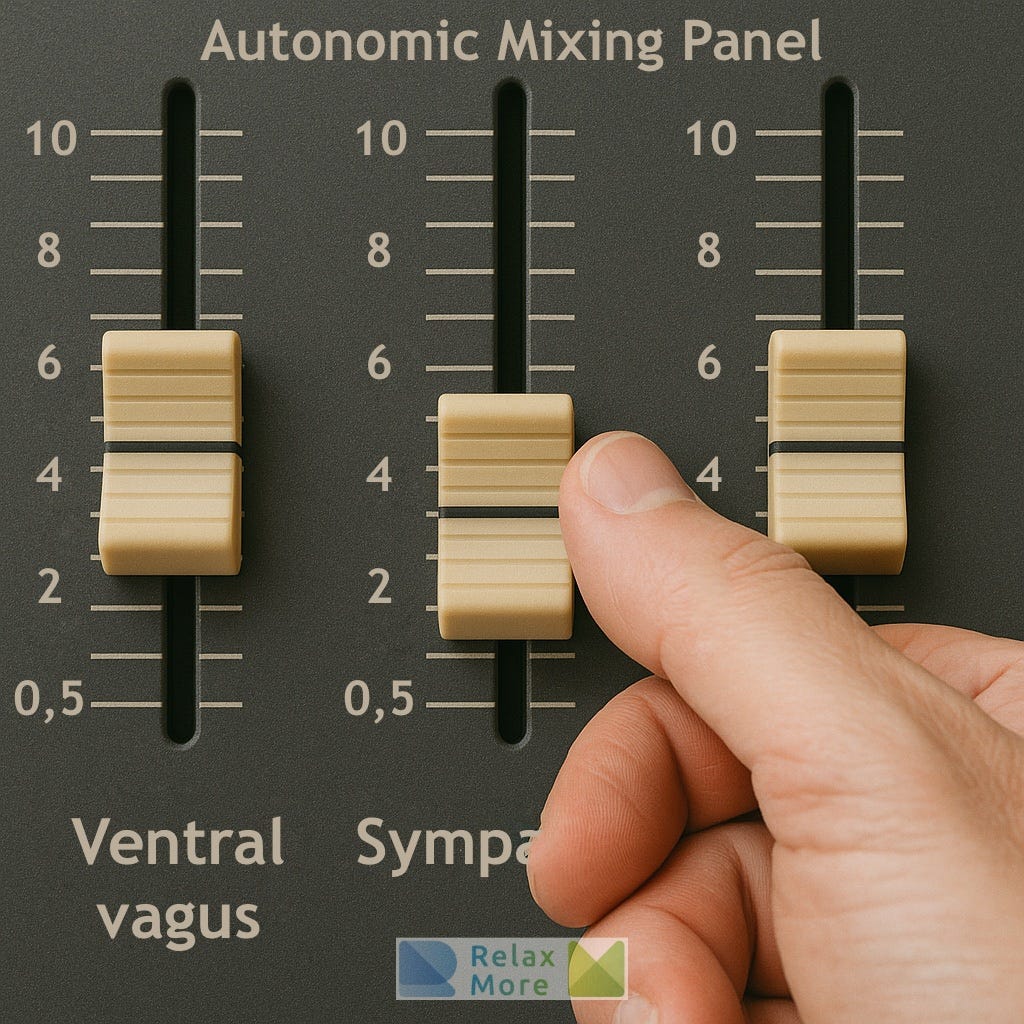

Co-regulation and neuroception belong together in first place. That’s chronologically much more accurate. The sense of safety (neuroception), which comes about partly through co-regulation, determines what autonomic setting the mixing panel gets, how you feel as a result, and what behavior you will exhibit. The autonomic state thus follows from neuroception and co-regulation.

There’s also quite a bit to say about co-regulation; that’s sometimes portrayed too simplistically as well, namely as regulation with the help of another person. That’s only half the truth. As I wrote in this article: self-regulation is also a form of co-regulation.

Back to the fixation on hierarchy for a moment. I also spent more time on hierarchy than on the other two pillars for a while, so I know the mechanism. But when I realized that as a professional I had more influence on the autonomic state by being more attentive to safety through neuroception and co-regulation, it made my polyvagal understanding much deeper.

By fixating on hierarchy, you make PVT too simple and make things unnecessarily difficult for yourself. Check out this image of the hand operating the autonomic mixing panel. The hand is neuroception. Without neuroception/hand, nothing changes!

Ventral Is Good and Dorsal Is Not

A third oversimplification that has gone too far—and could even cause harm to clients—is the idea that the goal is to have the ventral vagus ‘on’ as much as possible. And that you should try to prevent your dorsal vagus from being too active. In my view, there are three causes for this idea:

The ladder suggests that being at the top is better than being at the bottom. At the top is usually the ventral, green area, usually with a figure that appears active. Therapists who think they have enough polyvagal knowledge if they understand the ladder don’t sufficiently counter this.

People still too often think from the idea that polyvagal theory is about stress, threat, and trauma. But that’s (literally!) only half the story. The autonomic nervous system is active 24 hours a day, so even when there’s no threat. Good activity of the dorsal vagus is of great importance for our health and homeostasis. Moreover, the activation of the dorsal vagus in the face of threat is not wrong but adaptive (see next point).

This brings us to the confusion that the word hierarchy can cause. In the military, hierarchy means that one soldier is higher in rank than another and thus has more say. In PVT, that’s actually also the case: the ventral system “downregulates” the other two (older) systems. That is indeed hierarchical, but it’s not a value judgment! The ventral system is not more important than the sympathetic or dorsal system! (A third reason for an autonomic mixing panel.)

It’s therefore not good if clients start thinking that their nervous system is responding incorrectly when they’re not ventral or when dorsal is somewhat more or even very much activated. Your nervous system isn’t broken; it’s adaptive and adapts to circumstances, using the information it receives and its interpretation based on what it has experienced in the past.

A Bit More About the Ladder

The polyvagal ladder was conceived in the 2010s by Deb Dana, a therapist and author, who played a major role in translating polyvagal theory into the practice of the therapy room. This has been truly important for raising awareness of PVT. You can’t blame Dana or her ladder for the shortcoming that applies to every model, namely that it’s a simplified representation of reality. That’s logical! Because if reality were so simple that we could understand it without a model, we wouldn’t need a model.

My autonomic mixing panel is also a model and therefore also has shortcomings. That’s why I use multiple models in my two-day training, which somewhat compensate for each other’s shortcomings. In addition to Deb Dana’s Polyvagal Ladder (yes, so I use it too), I naturally use my own autonomic mixing panel, but also Dan Siegel’s Window of Tolerance (which I wrote about in this article) and the Activation Curve.

So my “grumbling” about the ladder isn’t entirely fair; I should actually be grumbling about the people who equate the ladder with polyvagal theory.

In Summary

This is how misunderstandings can arise that create the impression that polyvagal theory is a simple ladder model in which we can learn to move upward (please do!) or downward (oops, careful!).

Because the dorsal “area” is considered dangerous, the perception can arise that normal and protective reactions of the nervous system are not good or undesirable, and there’s a risk of excessive pathologizing (we call something sick that is actually not a disorder). People start thinking their nervous system is “broken,” when in fact it’s trying to protect them.

By fixating on hierarchy, neuroception and co-regulation receive less attention than they deserve. After all, it’s neuroception that provides the information to regulate our autonomic state. The question of how we can make it safe enough for ourselves or our clients and where our influence on this lies is a more important question, because the answer will help harmonize the autonomic state more.

So polyvagal theory is not simple, nervous systems are not broken, and the hierarchy is not hierarchical.

How Can I Learn More About This or Stay Informed?

I offer a two-day training for professionals (in Dutch) where we dive deep into it and regularly write about polyvagal theory.

Together with Cees van Elst, I provide a two-day masterclass on Polyvagal-Informed Guidance in (Coaching) Practice.

Additionally, the Polyvagal Institute Netherlands is working to promote PVT, provide good information, and develop teaching and course materials. Their newsletter is worthwhile, and they regularly organize Polyvagal meet-ups.

If you found this article worth reading and (not yet) feel like getting a paid subscription, you can always treat me to a cappuccino!