Researchers at the University of Calgary discovered that stress is more than just contagious: it changes the brain at the cellular level. And from a polyvagal perspective, we now understand why this happens and what it means for our social connections.

Research in Mice

In an important study published in 2018 in Nature Neuroscience, Jaideep Bains, PhD, and his team at the Cumming School of Medicine’s Hotchkiss Brain Institute (HBI), a division of the University of Calgary, discovered that stress we pick up from others can change our brain in exactly the same way as real stress does. The study convincingly demonstrated this in mice, and by now (2025) much follow-up research has been conducted that has further expanded these findings.

“Brain changes resulting from stress reinforce many mental disorders such as PTSD, anxiety disorders, and depression,” says Bains, professor in the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology and member of the HBI. “Recent studies show that stress and emotions can be ‘contagious.’ Whether this also has lasting consequences for the brain was not yet known at the time.”

One Stress, Two Effects

Bains’ team studied the effects of stress in pairs of mice. They removed one mouse from its partner and exposed it to moderate stress, after which the mouse was returned to its mate. They then examined the response in a very specific set of brain cells (the so-called CRH neurons, or corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons) that play a key role in the brain’s response to stress. These neurons are located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN; a nucleus of the hypothalamus—a brain region of our oldest brain that plays an important role in various autonomic regulatory processes—located beside one of the brain ventricles, which are fluid-filled spaces) and coordinate both behavioral and endocrine (hormonal) responses to stress.

They discovered that the brains of both mice—including the half of the pair not exposed to stress—changed in the same way as a result of the stress. Lead researcher Toni-Lee Sterley: “It is quite remarkable that the CRH neurons of the partners who were not exposed to stress underwent changes that were identical to those we found in the stressed mice.”

What specifically happened here was a form of what we call synaptic metaplasticity; you could say the plasticity of plasticity. Normally, synapses (the connections between neurons) become stronger or weaker through use; that’s ‘ordinary’ synaptic plasticity. But with metaplasticity, the sensitivity of the synapse itself changes: it becomes more or less receptive to future changes. The researchers discovered that certain synapses on the CRH neurons were ‘primed,’ making them heightened in sensitivity to future stressors. This priming mechanism turned out to occur both after real stress and after transmitted stress.

An ‘Alarm Pheromone’

To understand precisely how this stress transmission works, the team conducted two clever experiments with optogenetics—a technique that allows you to switch specific neurons on or off with light:

Experiment 1 - Switching Off CRH Neurons:

When they exposed a mouse to stress but simultaneously switched off the CRH neurons with light, something remarkable happened: the partner was not subsequently stressed. Despite the first mouse having experienced stress, no transmission occurred. The CRH neurons thus appear necessary for transmitting stress.

Experiment 2 - Artificially Activating CRH Neurons:

Even more striking was the reverse experiment. They took a mouse that had experienced no stress at all but artificially activated only the CRH neurons with light. The result: the partner reacted as if the first mouse was stressed! Even without anything stressful actually having happened, the stress was transmitted.

These experiments showed that the CRH neurons secrete a kind of ‘alarm pheromone’—a chemical warning signal. The chain works as follows: stress activates the CRH neurons → which stimulate the secretion of the pheromone (probably via the anal glands) → the partner detects this signal → whereby the partner’s CRH neurons are also activated → and the partner also feels stressed.

The activation of CRH neurons in both mice—both sender and receiver—proved essential for this transmission. This way, a stress signal could even spread sequentially to multiple members of a group: from the originally stressed mouse to the partner, and from there even to a third mouse that had never experienced the original stressor. A kind of chain reaction of stress.

Social Buffering: A Sex-Specific Phenomenon

In addition to stress transmission, the team also discovered a buffering effect, but this proved to be very selective and sex-specific. In female mice that had experienced stress, the metaplasticity of the CRH neurons was almost halved when they subsequently spent time with a non-stressed partner. It’s as if the presence of a relaxed partner ‘dilutes’ the stress effects and makes them diminish faster.

In male mice, however, this buffering effect did not occur. For them, only stress transmission applied, without the protective effect of social interaction. This sex difference aligns with the ‘tend-and-befriend’ pattern we see in many mammals: females more often seek social support when stressed, which can be evolutionarily advantageous for protecting offspring.

This means that social networks can have a dual effect: they can spread stress (in both sexes) but also provide protection—at least, it seems, especially in females. In males, the social network in this research functions more as a transmission channel than as a buffer.

Newer Insights: CRH Neurons as Integrative Hubs

Since the original 2018 research, much follow-up research has been conducted on the role of CRH neurons in stress and behavior. An important review from 2022 in Physiological Reviews describes how CRH neurons are not just end organs for the stress response but versatile ‘integrative hubs’ that play a central role in:

Behavioral Control: Studies from 2020 (Daviu et al., Nature Neuroscience) show that CRH neurons can ‘encode’ the degree of control an organism has over a stressor. Stress with high controllability increases the anticipatory activity of CRH neurons, leading to more active coping strategies (such as fleeing). Stress with low controllability leads to passive strategies (such as freezing).

Physiological Memory: Research from 2023 (Nature Communications) shows that CRH neurons possess a form of ‘physiological memory.’ They remember both negative and positive experiences in different ways. With negative experiences, weaker neurons are actually activated more strongly during recall, while positive experiences lead to reduced activity. This memory can persist longer than the behavioral response itself.

Habituation: A study showed that CRH neurons strongly habituate to repeated presentation of the same stressor, but not to new stressors. This habituation is largely independent of corticosteroid feedback, suggesting it’s a local mechanism.

The Polyvagal Connection: Neuroception and Social Engagement

From a polyvagal perspective, this research gains a fascinating dimension. Polyvagal theory, developed by Stephen Porges, provides a framework for understanding how our autonomic nervous system supports social engagement, emotional resilience, and adaptive physiological responses. Besides the three hierarchically organized autonomic states the theory describes, neuroception and co-regulation are central concepts.

Neuroception: The Unconscious Safety Detection System

A core concept in polyvagal theory is neuroception: the unconscious process by which our nervous system continuously scans the environment for signals of safety, danger, or life threat. Neuroception determines which autonomic state is activated, without requiring conscious awareness. It’s a ‘bottom-up’ process that works via temporal cortex areas that decode biological movement and detect the intentionality of social interactions.

The research on stress transmission via pheromones fits perfectly into this neuroceptive framework. The alarm pheromones released by stressed mice form chemical signals that are detected by the partner through neuroception. This detection automatically triggers the activation of their own CRH neurons, causing their autonomic state to shift from safety to defense.

The Social Engagement System in Action

Polyvagal theory describes the existence of a ‘social engagement system’—an integrated network that functionally links the control of facial muscles, vocal tone, and head movements to ventral vagal regulation of heart and breathing. This connection enables social interactions to directly influence our physiological state.

The stress transmission that Bains and colleagues discovered is essentially a chemical parallel of this social signaling system. Both mechanisms—visual/auditory signals and chemical signals—function as channels for co-regulation: the mutual process by which organisms influence each other’s autonomic state.

Co-regulation and Social Buffering

A crucial insight from polyvagal theory is that social connection is not just pleasant, but a fundamental biological necessity for mammals. The ability to influence each other’s autonomic state—co-regulation—is essential for our survival and wellbeing.

The sex difference in social buffering that Bains’ team found (females yes, males no) aligns with the ‘tend-and-befriend’ pattern that Taylor et al. described: females respond to stress more often by seeking social connection than with fight-flight, which is evolutionarily advantageous for protecting offspring (source).

Recent research (2024) on polyvagal applications in therapy emphasizes that when neuroception is chronically set to danger—even in the absence of actual threat—the body gets stuck in defensive autonomic states. This corresponds precisely with the finding that transmitted stress causes the same synaptic changes as real stress: the brain doesn’t distinguish between direct threat and socially perceived threat.

The Polyvagal Catch-22 of Stress Contagion

Here an interesting tension arises. The mechanism that transmits stress via CRH neurons and alarm pheromones evolved as a survival strategy. It warns group members of danger without them having to experience the threat themselves. This saves energy and can save lives.

However, in our modern 24/7 stressed world, this mechanism overshoots its goal. When people are constantly surrounded by stressed individuals—at work, in traffic, on social media—we’re continuously bombarded with stress signals. Our neuroception keeps detecting danger, causing:

The ventral vagal brake on the sympathetic system to release

We get stuck in mobilization or shutdown

The social engagement system goes ‘offline’

Access to social co-regulation becomes blocked

This creates a vicious circle: chronic stress impedes precisely the social connection we need to recover from that stress.

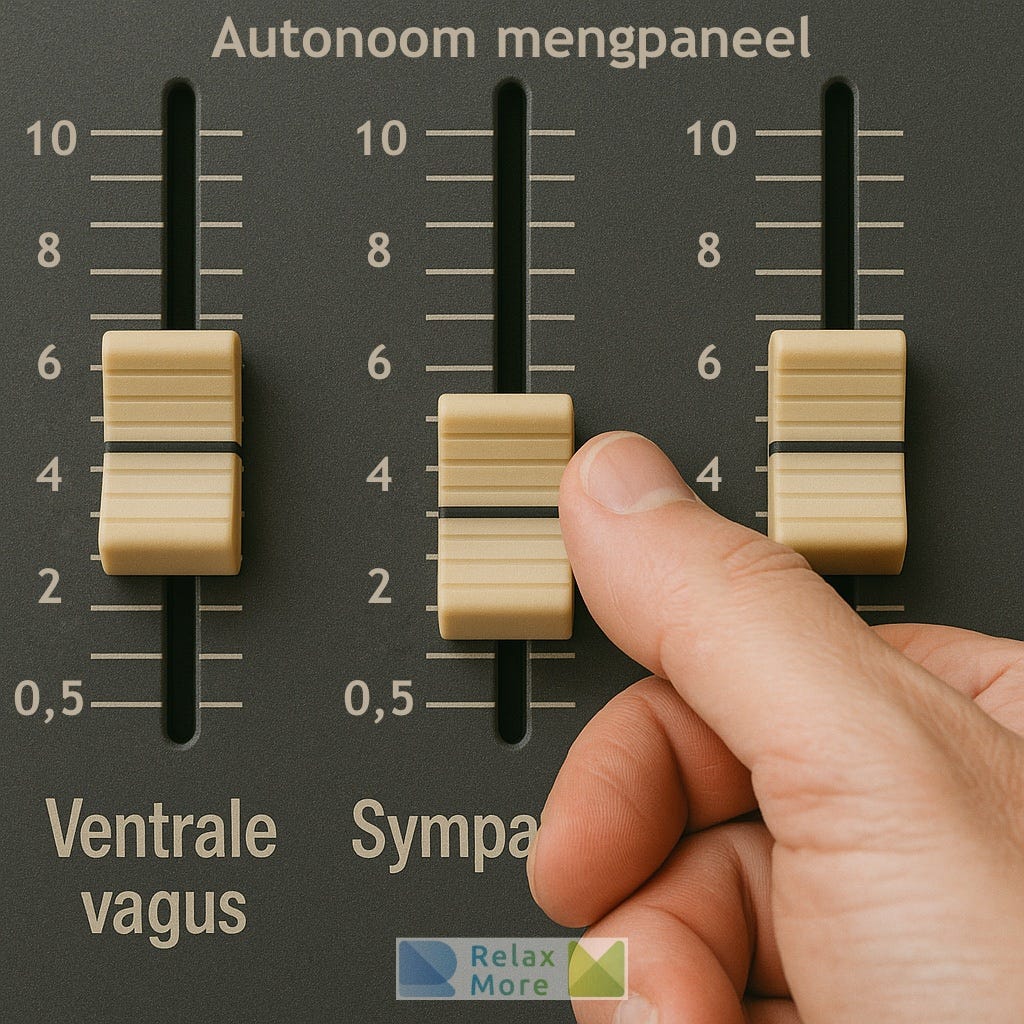

The Autonomic Mixing Panel: Flexibility as Key

With my own model of the ‘autonomic mixing panel,’ in which we consider autonomic states not as discrete states but as a mix of different activation levels (which they also are), I hope to make it clearer that health is not about avoiding stress signals, but about maintaining flexibility. The CRH neurons that Bains studied show exactly what happens with stress and how loss of flexibility occurs: they become ‘primed’ and remain heightened in responsiveness, even when the actual threat has long passed.

Restoring flexibility requires:

Conscious co-regulation: actively seeking out people and an environment that emit safety signals

Activating the ventral vagal complex: through soft eyes, breathing, movement, voice, connection

Restoring appropriate neuroception: learning to distinguish between real danger and false alarm

And in Humans?

Although this research focused on mice, according to Bains the same can occur in humans. “We also communicate all our stress to others, often without realizing it ourselves. There is even some evidence that stress symptoms are elevated in acquaintances and friends of people with PTSD. Partners can develop secondary traumatic stress and experience general stress, while children are at increased risk for internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems (source). On the other hand, being able to sense someone’s emotional state is an important part of establishing and maintaining social relationships.”

The research by Bains’ group, together with more recent work on stress controllability (source), physiological memory (source), and CRH neurons as integrative hubs (source), suggests that stress and social interaction are connected in a far more complex way than we thought. The consequences of this connection can persist for a long time and still influence our behavior at a much later time. From a polyvagal perspective, we understand that these effects are mediated by the self-reinforcing effect of neuroception and the reduced accessibility of our social engagement system.

Afterthought: From Survival Mechanism to Modern Health Problem

Imagine if this effect is indeed demonstrated in humans, which wouldn’t surprise me. It would contain a certain irony. After all: a system that enables us to warn each other non-verbally of danger and that could have been life-saving from an evolutionary perspective, actually overshoots its goal in today’s continuously stressed world and constantly puts us on alert.

Chronic stress is rapidly becoming the biggest health problem. The environment you’re in might become of great importance. I see it with participants in my groups: for people who live or work in a very stressful environment, it’s sometimes extra difficult to apply what they manage quite well in the lessons to the practice of daily life.

From a polyvagal perspective, this is completely logical: their neuroception keeps signaling danger in that environment, their CRH neurons remain primed, their autonomic flexibility is reduced, and co-regulation with colleagues reinforces the stress rather than buffering it.

It’s no wonder I wrote earlier that mindfulness training can also be used as a ‘pacifier’ for stressed employees, so that the conditions at work itself don’t have to be addressed. But from a polyvagal perspective we know: if the environment continuously signals danger that is registered via neuroception, then individual regulation techniques will only provide temporary relief. Real change requires creating a safe context, so that the ventral vagus can become active again and downregulate the older systems and the entire autonomic nervous system can function in balance again.

Stress: The New Smoking

And an analogy comes to mind. Where in the 1950s we had no idea of the negative effects of smoking, a decade ago we didn’t yet fully realize how bad stress really is. Now it turns out stress is not only unhealthy, but a form of ‘mental secondhand smoke’ can also arise that affects those in the vicinity of a stressed person.

I don’t like visiting places where people smoke. Well, nowadays many people are willing not to smoke when there are visitors, so that’s increasingly less of a problem. But whether you can also switch off your stress so as not to ‘infect’ visitors with your stress—that seems like a more difficult task.

It seems good to me that awareness arises of the different ways in which stress transmission takes place, just as ‘secondhand smoke awareness’ once emerged, that we invest more in co-regulation and social safety, and that we might even create ‘smoke-free’ zones where the ventral vagal complex can come sufficiently online again.

We’re heading into interesting times, in which we will hopefully learn that health is not only an individual, but also a collective, social, and relational matter.

And What About Positive Emotions?

If stress is so powerfully contagious through biological mechanisms, the question naturally arises: does this also apply to positive emotions? The answer is nuanced and illustrates a fascinating asymmetry in our research on emotional transmission.

Yes, positive emotions are also ‘contagious.’ Research by Nicholas Christakis (Harvard) and James Fowler (UC San Diego) showed that happiness spreads through social networks up to three persons removed (so the friend of your friend of your friend; source). A happy friend who lives within a mile and a half of you increases your chance of happiness by about 9%. Experimental research on Facebook confirmed that when people see more positive content, they themselves produced more positive posts (source).

Laughter proves to be one of the most contagious emotions. We all know the phenomenon: someone starts laughing, and before you know it the whole group is roaring with laughter, sometimes without knowing exactly why. This emotional contagion works largely via mirror neurons and the automatic mimicking of facial expressions, vocal tone, and body language.

A Striking Inequality

But yes: while for stress transmission in mice we now better understand the neurobiological mechanisms (the CRH neurons, the alarm pheromones, and the synaptic changes), comparable research for positive emotions is largely absent. In rodents, transmission of positive emotions is barely studied, while fear, depression, and stress are extensively researched.

This inequality is possibly not accidental. From an evolutionary perspective, negative emotions are crucial for survival: a missed danger signal can be fatal. A missed opportunity for joy is less risky. Our brain therefore has a negativity bias: negative information attracts more attention, is better remembered, and weighs more heavily in decisions. This perhaps also explains why we study the transmission of stress more thoroughly than happiness transmission.

This also aligns, as described throughout this article, with how stress transmission works. Stress triggers defensive autonomic states that prepare us for danger—a fast, automatic response that runs via subcortical routes. Positive emotional contagion works via the social engagement system and requires signals of safety: you must feel safe enough to be open to another’s joy. In other words: negative contagion also works when you’re not stressed (it can break through your safe state), but for positive contagion you need an active and ‘online’ ventral vagal complex (you must already be safe enough to be open to someone else’s joy).

A Call for Balance

We’re actually not investing enough in understanding how safety, connection, and joy spread. If we know that one stressed mouse can influence other mice via pheromones, then we should actually investigate just as thoroughly how a relaxed, playful mouse can influence others.

Instead of primarily focusing on preventing stress transmission, we could also learn how we can actively facilitate positive emotional contagion. There is evidence that positive emotions can be transmitted, but most research focuses on fear/depression/stress (source).

Perhaps creating “islands of safety” in stressed environments not only yields stress buffering, but also makes active transmission of wellbeing possible. A polyvagal cascade in a positive direction.

If you found this article worth reading and (not yet) feel like getting a paid subscription, you can always treat me to a cappuccino!