Introduction

The number of COVID cases is rising again (this article was published in early January 2026) and appears to be approaching (almost) epidemic levels.

The good news is that there is increasing evidence for the importance and effectiveness of qigong in the treatment and prevention of COVID and long COVID. Below I describe two studies. One dates from early in the pandemic (2020): Qigong for the Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 in Older Adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, May 2020.

“Potential mechanisms of action include stress reduction, emotion regulation, strengthening of respiratory muscles, reduction of inflammation, and improved immune function.”

The second study was published in November 2025 in BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies: Experiences with Qi and changes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19.

“Approximately three-quarters of participants reported improvement in one or more post-COVID symptoms (referred to in the study as PASC)1, most commonly fatigue, brain fog, and sleep quality, and 85% reported improved well-being.”

1—Qigong for the Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 in Older Adults

Qigong exercises are known for their beneficial effects. Through mindful and meditative guidance of the breath, combined with body postures and/or movements, stress-reducing and emotion-regulating effects are described. In addition, much has been written about better-developed respiratory muscles and positive effects on immune defense and recovery from illness.

The researchers who wrote this article wondered what is known about the effects of qigong on respiratory infections, and more specifically on COVID-19. How did they approach this?

Study design

First, the researchers looked at several medical aspects that can occur with a severe COVID-19 infection. Some medical problems that are regularly described—and that we have seen and heard in the media at the time—are that …

People with reduced immunity (due to underlying conditions and/or old age) are particularly vulnerable;

A COVID-19 infection can be accompanied by a cytokine storm. This is a serious and often fatal dysregulation of the immune system, whereby the immune cells cause an inflammatory response throughout the body. The immune system essentially goes “haywire,” becoming uncontrollable;

Serious breathing problems can develop;

Recovery from severe COVID-19 requires a lot of energy, respiratory training, exercise and muscle strength training, and also psychological support;

We now know that some people experience persistent and sometimes severe residual symptoms in terms of fatigue and energy levels.

Based on this knowledge, a number of search terms were chosen relating to these medical problems2, and these were combined with a number of qigong-related search terms3. Because of the typical respiratory problems that can occur with COVID-19 infections, searches were naturally also conducted for “respiratory infection” and “respiratory rehabilitation.”

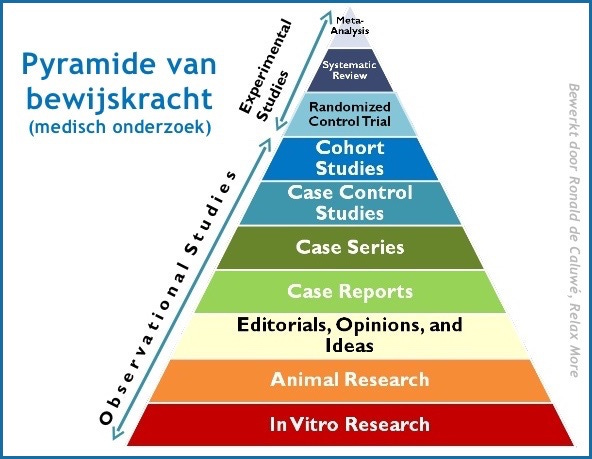

These search terms were applied to several medical databases, and the articles found were then evaluated. If the article was a clinical review or a systematic review4 and was written in English or Chinese, it was included. This ultimately turned out to be 45 articles.

About qi and qigong

Naturally, the researchers explain in their article what is meant by qi and qigong. I will briefly summarize what they describe.

Qi

This is the energy that flows through the meridians and ensures that we can carry out our daily life activities. There are different types of qi. The circulation of qi is involved in all life processes. Many disease processes are a result of disturbed qi flow.

Qigong

This is the training of being able to regulate qi. It may be seen as mind-body training to regulate body, mind, and breath so that health is promoted and disease is prevented or cured.

The exercises consist of slow movements or stationary postures, combined with breathing instructions and meditation, often in the form of visualization and/or concentration.

These exercises have a history of more than 4000 years and are deeply intertwined with Traditional Chinese Medicine and Taoist teachings. However, the term qigong was only coined in the 1950s for this beneficial body-mind discipline.

Research has already shown that qigong can be very supportive for many (including chronic) diseases that fall under internal medicine, as well as for many psychosomatic conditions. Think of asthma, stomach disorders, fibromyalgia, diabetes, and high blood pressure. In addition, qigong is used as health support for older people with mood disorders, cognitive decline, and dementia.

Classification of qigong

Let’s take a brief detour to mention and classify some forms of qigong. The study refers to dynamic or active qigong and meditative or passive qigong.

Active qigong includes Tai Chi Chuan, Yi Jin Jing (muscle and tendon strengthening exercises), Wu Qin Xi (the five animal exercises), Liu Zi Jue (the six healing sounds), and Ba Duan Jin (the eight brocade exercises). All exercises that are known and practiced worldwide.

In passive qigong, the body does not move or moves little (which does not mean that the body is unimportant!) and more work is done with meditation and breath. It is more a mental than a physical training.

For many people, active qigong is easy to learn, and given its physical components, active qigong seems more suitable as training for the musculoskeletal system, including the respiratory muscles, than passive qigong.

Beneficial effects of qigong on respiratory infections

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), a respiratory infection is classified among diseases caused by external pathogens. An imbalance arises that our immune system must correct with the help of so-called “wei qi,” the qi or energy that represents the immune system according to TCM. If the wei qi is sufficiently strong, the infection can be fought.

Older people often have deteriorated organ functions due to pre-existing chronic conditions. As a result, their wei qi is no longer as strong, they are more susceptible to pathogens, and an infection will also progress more severely.

Because qigong also strengthens wei qi, it may prevent respiratory infections, positively influence their course, or promote recovery.

Possible mechanisms of action of qigong for respiratory infections

The numbers in [square] brackets that appear in this section refer to the studies listed in the article’s bibliography.

1) Stress and emotion regulation

Every illness causes a stress response in the body. In addition, stress can also arise from worries you may have about being sick. The physiological changes observed by Benson during meditation [13] show that meditation can counteract stress. Benson refers to this as a “relaxation response.”

Similarly, it has been found that meditative movement through qigong reduces the amount of stress hormones in the blood [14]. Another effect is that practitioners become less mentally reactive, so that negative thoughts have less grip5. A dampening effect on the hormonal stress axis—which involves the hypothalamus, pituitary gland (two old brain structures), and the adrenal cortex and which directly affects the functioning of the autonomic nervous system—means that inflammatory reactions are less severe [15].

A large study found that qigong reduced feelings of anxiety and depression in people with COPD (chronic lung disease) [16]. Also important to mention is that practicing qigong can give a sense of control (you are doing something positive for your health yourself) and togetherness when you do it in a group [17, 18].

2) Strengthening the respiratory muscles

Liu found in research that qigong had measurable effects on grip strength, jump height, and toe strength in older people [19], thus a positive effect on muscle strength. Specifically training the abdominal muscles led to a stronger diaphragm (the most important respiratory muscle) [20]. Wu also found stronger respiratory muscles in COPD patients who trained in Liu Zi Jue for 3 months [21].

3) Inflammation reduction

Qigong can have a positive effect on both inflammatory factors and inflammatory responses. For example, it has been found, among other things, that a 6-month Tai Chi program led to a lower IL-6 level (Interleukin 6, an inflammatory protein), while this had previously been much too high in the participants [22].

Other studies show lower CRP levels (an inflammation marker), lower production of pro-inflammatory substances, and higher levels of anti-inflammatory substances (cytokines) [24, 25].

4) Improving immune function

The improvement of immune function through qigong manifests itself in both the specific and non-specific immune response.

We start with the non-specific immune response. Here we see that qigong increases the number and activity of immune cells in the blood. T-helper cells are often mentioned here, as well as Natural Killer cells; and this often particularly concerns substances that promote the production and/or function of these important immune cells [24, 26, 27].

It is fascinating to read that Nieman concludes that moderately intensive exercise can reduce the risk of respiratory infections, while intensive exercise (”heavy exercise”) can actually increase this risk [28].

We talk about the specific immune response when we look at an increase in immune cells and levels of immunoglobulins (antibodies). We see that various positive results have been found. This always concerns a significant (more than coincidental, thus very likely caused by the intervention {in this case qigong}) increase in dendritic cells [29], B-lymphocytes (both a certain type of immune cell) [30], and IgA, IgG, and IgM (important immunoglobulins {Ig}) [31].

It is notable that these improvements are greater the longer (several years) one practices. Fortunately, it was also seen that positive effects were measurable after a month, which is useful to know in relation to an acute COVID-19 infection.

A small side note, but perhaps relevant for vaccinations, is that research [32] shows that qigong practitioners had a greater immune response (thus received more protection) after a chickenpox vaccination. Another study [33] showed that after a flu vaccination, the magnitude and duration of the antibody response was much better in Tai Chi practitioners than in the control group.

Clinical evidence for the effectiveness of qigong in respiratory infections

Prevention

There are a few studies on the preventive benefits of qigong for respiratory infections. There is the study by Hu et al. [34], which proved that qigong practitioners had significantly fewer respiratory infections than the control group that went jogging. The research lasted two years, and the effects of qigong only increased (thus the differences between the two groups increased).

Wright et al. [35] conducted research on swimmers who also practiced qigong and found that the more qigong was practiced, the milder the cold and flu symptoms that occurred.

Treatment

A few studies have been found on the application of qigong in the acute phase of respiratory infections. These studies show a shortening of infection duration, but no demonstrable reduction in the prevalence (frequency of occurrence) of respiratory infections.

Recovery and rehabilitation

Serious respiratory infections often have a prolonged recovery period, even in younger people. Research on the effectiveness of qigong in recovering from respiratory infections is also not very abundant, but we are not completely empty-handed! Various studies show the supportive effect of qigong.

There is Tong’s meta-analysis of 10 studies, which demonstrates that qigong improves the lung function of COPD patients (chronic lung disease, particularly chronic bronchitis and pulmonary emphysema). In addition, an improvement in strength and fitness was also found in these people, as well as an improvement on an important quality of life scale.

The researchers found that Ba Duan Jin and Yi Jin Jing in particular provided improvement and that the effect of Liu Zi Jue was not measurable. However, another study [38] shows that Liu Zi Jue is indeed effective for COPD patients.

Finally, I mention the research by Chen et al. [39], which demonstrates that lung function improved and hospital admission duration decreased in patients with bronchitis who practiced Ba Duan Jin. Naturally, compared with a control group that did not do these exercises.

And further…

The article continues with a section on how to learn qigong and tips for practice. Since my article is already long enough and you can find information about qigong elsewhere on the website, I will leave that out of the discussion here.

Recommended forms of qigong

I could also do that with the part about which qigong form to recommend. Yet I think it is worthwhile to mention that the authors believe that Ba Duan Jin, Liu Zi Jue, and abdominal breathing exercises are most suitable. I am particularly pleased with the mention of Ba Duan Jin, the “Eight Brocades,” because we often do these during my qigong classes. I must confess that I have no idea why abdominal breathing is suddenly mentioned as a separate discipline; it is not mentioned anywhere else in the entire article.

According to the authors, these three forms of exercise are often applied, they are easy to learn, not too high in intensity, and they can be practiced in a smaller space. This makes them suitable for home practice, for example during quarantine.

There follows another section about these three different forms, which I will now leave out of consideration.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that the evidence suggests that qigong could potentially be useful in the prevention, treatment, and recovery from respiratory infections, including COVID-19. Older people in particular could benefit from it. Further research is needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of qigong in these contexts.

Final reflections

The researchers took quick action when the corona crisis broke out. It is a specific topic, so it is not surprising that they did not find hundreds of studies. Regarding COVID-19, there is no research available at all regarding the effect of qigong. This means that the researchers understandably have to build on research into diseases and symptoms related to COVID-19. This naturally carries a risk, namely that they have made incorrect assumptions and conclusions.

However, as someone with some expertise, I do not read anything very surprising or striking in the research, and I can understand the reasoning and conclusions followed.

Three more observations:

I read that in many of the consulted studies, the effects are only measured after a program of 12 or 24 weeks, or even half a year. In addition, it is frequently found that longer practice leads to more effect. Qigong practitioners naturally know that only repeated practice leads to results, so that is not strange to them. It does raise the question for me of when exactly the first effects are measurable and noticeable. And I think this is also relevant for people who are (again) dealing with a COVID-19 infection.

“More research is needed.” Almost every scientific article ends with this remark. And that is not just to keep researchers busy with new grants. Science is never finished. It doubts and searches for footing in swamps full of uncertainties. Very frustrating for those who want to know exactly “how things are.” And when you think you know how things are, new research can undermine that certainty. This also applies to this research, especially because the subject is so current and still little researched.

I also think it is worth mentioning what was NOT found in the analysis of the 45 articles, namely that qigong could be harmful. Nowhere in the article are negative effects of qigong on respiratory infections mentioned.

A pleasantly readable and well-developed article, interesting to study, carefully conducted research with current value, and therefore important.

Source

Source article: Qigong for the Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Infection in Older Adults.

2—Experiences with Qi and changes in postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) symptoms with qigong

A qualitative study

Many people with post-COVID (PASC) have persistent symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive sluggishness (”brain fog”), shortness of breath, and sleep problems. There is (still) no well-validated treatment. The authors therefore explore qigong as a possible complementary approach, specifically a combination of external qigong and an internal, very calm qigong form. What is special about this study is that it is not primarily about measured values but about the participants’ stories: what did they feel, how did they understand “qi,” and what changes did they notice in symptoms and well-being? We are then talking about a so-called “qualitative study,” a very different kind of research than the first.

The intervention

Participants received weekly sessions of approximately two hours for six weeks in small groups (2-9 people). The program consisted of:

External qigong: a form of energetic healing. In this study, the practitioner worked without touch, with hands at a distance (at least ~15 cm) from the body, usually from head downward. The duration and movements varied per person and per session, depending on what the practitioner thought they perceived.

Internal qigong (guided exercise): a seated, more meditative exercise with three phases: breathing to the dantian (lower abdomen), experiencing a “qi ball” between the palms, and connecting with “universal qi” (with attention to crown/hands).

Who participated?

The 26 participants were 25-79 years old, with an average age in the mid-50s. Approximately 73% were female; the majority were white. The average duration of post-COVID symptoms was approximately two years (average 24.7 months; range 4-47). At baseline, the most commonly reported symptoms were fatigue (88%), brain fog (73%), and shortness of breath (65%), in addition digestive complaints, muscle pain, headaches, heart palpitations, dizziness, and sleep problems, among others.

Design and approach

This qualitative analysis is embedded in a larger study, which is not discussed further now. For the qualitative study, all 26 participants who completed the program were interviewed with a semi-structured questionnaire within two weeks after the last session. The interviews lasted roughly 8-42 minutes and were transcribed and analyzed through conventional content analysis. Multiple researchers coded the texts; any differences were resolved through a “tie-breaker.”

What did participants understand by qigong?

A key finding is that participants often described qigong as a form of “working with energy” that helps release blockages, promotes recovery, and brings calm. Some used very concrete images (“energy centers,” “flow”), while others referred to the practitioner’s explanation (for example, releasing “held energy/trauma”). And a small minority said honestly, I don’t really understand it well enough to explain it; which in itself is also informative: not everyone has a narrative for their experiences.

Experiences with feeling qi

Almost everyone (92%) reported that they could perceive qi during the sessions. The descriptions varied but had striking similarities: warmth or cold, tingling, a breeze, pressure/heaviness, “magnetism,” static electricity, or a “ball” between the hands. Many participants felt it mainly in the hands, sometimes also throughout the body or on the crown. The experience was usually described as pleasant, not painful, and relaxing.

Changes in symptoms and well-being

PASC symptoms

Approximately 73% of participants reported improvement in one or more post-COVID symptoms during the program. This most often concerned energy/fatigue (coded by researchers as improvement in 72% of participants), followed by brain fog (39%) and sleep (20%). In addition, improvements were also mentioned in digestive complaints, loss of smell, cardiac arrhythmias/palpitations, joint pain, headaches, and mood, among others. The degree of improvement varied from mild and temporary to (in some stories) very pronounced and life-changing, and there were also participants who experienced little to no change.

Well-being

Even more striking is that 22 of the 26 participants explicitly reported an improvement in well-being (the remaining responses were not clear enough for the coders to classify, but no one said unequivocally “no improvement”). The improvement was not only linked to symptom reduction but also to more calm, a more meditative state, and the feeling of having a usable tool to apply themselves (for example, for chest pain or waking up at night). Multiple participants also described a shift in attitude: symptoms were sometimes still there, but they became less frightening or less all-determining; there was more resilience, more hope, and less “sense of doom.”

The group factor: “I’m not the only one”

Almost everyone emphasized the positive aspect of the group element: recognition, validation, exchange, and simply being together in one space with people experiencing the same thing. A few participants indicated that they met someone else with long COVID for the first time ever and that this in itself was healing. The authors place this in the broader literature on group interventions for chronic conditions, and point out that PASC is often accompanied by isolation.

A remarkable observation: qi perception and improvement

The researchers compared reporting of “feeling qi” with symptomatic improvement. Of the participants who did report some qi perception, 79% also had improvement in PASC symptoms. The two participants who could not feel qi also reported no symptom improvement. The authors are cautious: this does not prove causality and does not say that qi perception is “necessary,” but it is an intriguing pattern that calls for follow-up research.

Limitations and what you can and cannot conclude from this

This is a pilot with a small sample, one practitioner, and a multimodal program (external qigong + internal self-exercise + group). Therefore, you cannot identify which component was responsible for the result, and you also cannot rule out that expectations, selection (people who are open to such an approach), context (Saturday morning, quiet clinic), and the group itself played an important role. At the same time, the strength is that all participants were interviewed and that the analysis was explicitly aimed at carefully capturing the experiential world, including skeptical or unclear reactions.

Finally, the interview questions did not explicitly ask about changes in specific PASC symptoms, so the estimates of symptom-specific improvement may even be underestimates. Future studies should be conducted with a larger sample, with more ethnic diversity and multiple qigong practitioners. In addition, it would be interesting to blind participants to the intervention and/or test separate components of the intervention (e.g., external versus internal qigong versus the combination thereof).

Conclusion

This study is one of the few qualitative studies on qigong as a treatment for a medical condition. It offers a unique patient perspective on the effects of qigong, as well as insight into participants’ perception and understanding of qi. Most participants were able to perceive qi. The positive, preliminary findings of this study justify further research to evaluate the potential benefits of qigong in this patient population.

Source

Source article: Experiences with Qi and changes in postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) symptoms with qigong: a qualitative analysis of participants’ experiences in a pilot clinical trial.

If you found this article worth reading and (not yet) feel like getting a paid subscription, you can always treat me to a cappuccino!

The term PASC is also used in the Netherlands, especially in (international) scientific and policy contexts. For example: C-support explicitly mentions PASC alongside “post-COVID” and “PCS”. The RIVM also uses “Long COVID” and “PASC” side by side on its English-language page.

However: PAIS is increasingly seen in the Netherlands as an umbrella term for persistent symptoms after various infections, of which post-COVID is one. ZonMw uses PAIS in exactly this way. The Dutch Journal of Medicine (Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde) also recently wrote about “post-acute infection syndromes” along the same lines. The practical distinction:

PASC = specific: post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (i.e., post-COVID/long COVID).

PAIS = broader “umbrella term” for post-infectious syndromes in general (which includes post-COVID).

These search terms included, among others: immune function, inflammation, cytokine, respiratory muscles, abdominal breathing, stress, and emotion.

These search terms included, among others: Qigong, Qi Gong, Tai Chi, Tai-Chi, Taichi, Taiji, Yi Jin Jing, Wu Qin Xi, Ba Duan Jin, Liu Zi Jue (the latter four also in various spellings).

A clinical review is also referred to as an ‘update’. It involves a thorough but less in-depth investigation than a systematic review or meta-analysis (both at the very top of the evidence pyramid). Less in-depth often means the research has a somewhat broader scope, which is also the case here.

Updates are also more frequently published by content experts, in contrast to, for example, a meta-analysis, which can be conducted in a highly technical manner by non-experts.

The strength of evidence of a clinical review is not clearly defined in the pyramid shown above.

A quality that is especially cultivated through mindfulness training.